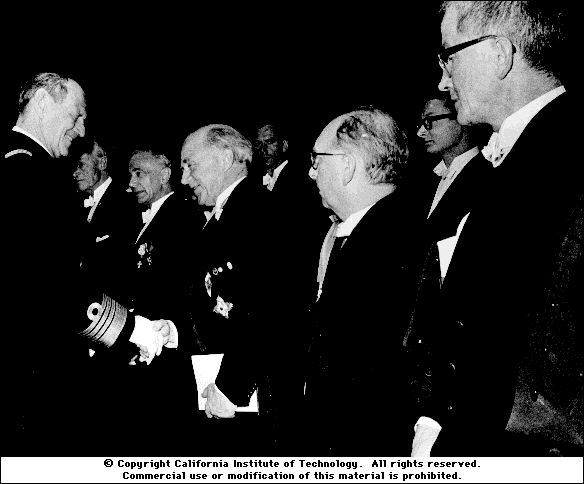

Delbruck at Caltech

In 1946 George Beadle, head of the biology department at

Caltech, offered Delbruck a position there. Delbruck accepted

and took the job in 1947. By 1950 his interests were

beginning to shift away from phage and toward sensory physiology,

but he did help launch the next wave of viral genetics: tumor

virology. Renato Dulbecco came to work with Delbruck and

was looking for a medically related problem. Delbruck

suggested he look at tumor viruses, nudging Dulbecco into an

extremely fruitful are of research in which he would win a

Nobel Prize.

Delbruck became interested in sensory physiology. His early

interests in light (from Bohr) and botany (from his days in

Bristol) resurfaced in his choice of the phototaxic response

of the fungus Phycomyces as a model system for sensory

perception. Delbruck lectured on Phycomyces to the CSH phage

course in the early 1950s and in the 1960s he initiated a

Phycomyces course there. But in this case Delbruck

oversimplified his problem. The model system he chose did not

have

enough in common with vision for it to provide much in the

way of useful insights into more complex systems. In

particular, the lack of sophisticated photoreceptors and

neurons created a qualitative gap between Phycomyces and seeing

animals.

Delbruck's early interest was in astronomy, but according to

his biographers he realized that German astronomy was at a

dead end in the 1920s and switched to quantum mechanics. He

interacted with many of the great German physicists of the

day, including Pauli, Einstein, and others. His advisor was

Max Born. In the summer of 1931 Delbruck went to

Copenhagen to work with Niels Bohr. A later colleague in the

"RNA Tie Club," George Gamow, was also there. Delbruck

returned often to Copenhagen and the open, critical,

scholarly atmosphere Bohr created among his group was a major

influence on Delbruck's own style of science. Delbruck then

had a Rockefeller Fellowship that took him to Bristol,

England. In 1932 he returned to Berlin to work with Lise

Meitner. The situation in Germany became intolerable, however,

and in 1937 he obtained a second Rockefeller Fellowship and

used it to move to Caltech. Shortly after Delbruck left,

Meitner discovered nuclear fission. Delbruck said his waning

interest in physics was by then holding back Meitner's group

and took indirect credit for allowing the discovery by

removing himself from Meitner's lab!

Delbruck's interest in biology is usually dated to his 1930s

sessions in Bohr's Copenhagen lab. Bohr had suggested that his

"complementarity" model (related to wave/particle

duality) might have biological analogues, and Delbruck thought

perhaps

new laws of physics might come out of study along these

lines. Specifically, in August, 1932 Bohr gave a lecture on

"Light

and life" at an international congress of light

therapists. In his talk Bohr suggested that life processes are

complementary to

the laws of chemistry and physics. This is said to have

sparked Delbruck's interest in biology and led him away from

physics.

In early 1937 Delbruck wrote to T.H. Morgan requesting a

research position. His early interest was in fruitfly genetics,

but

when he arrived in Pasadena he met up with Emory Ellis, who

introduced him to bacteriophage. Phage appealed to

Delbruck's physics-trained mind--he likened it to the

hydrogen atom of biology, the simplest genetic system known. He

and Ellis worked on phage at Caltech and in 1940 Delbruck

took a faculty position at Vanderbilt University in Nashvile. In

1941 he met Salvador Luria at a physics congress in

Philadelphia and the two men got excited about a collaboration.

The

met at Cold Spring Harbor that summer, after the annual CSH

Symposium, and thus began what became the "phage

group."

Delbruck and Luria collaborated on phage experiments. In 1943

they published a paper describing the ""fluctuation

test"."

This demonstrated that bacteria could spontaneously mutate in

response to phage and so develop resistance to them. That

year, Alfred Hershey, from Washington University, visited

Delbruck at Vanderbilt. Hershey was also working on phage

and was soon brought into the club.

In 1946 George Beadle, head of the biology department at

Caltech, offered Delbruck a position there. Delbruck accepted

and took the job in 1947. By 1950 his interests were

beginning to shift away from phage and toward sensory physiology,

but he did help launch the next wave of viral genetics: tumor

virology. Renato Dulbecco came to work with Delbruck and

was looking for a medically related problem. Delbruck

suggested he look at tumor viruses, nudging Dulbecco into an

extremely fruitful are of research in which he would win a

Nobel Prize.

Delbruck became interested in sensory physiology. His early

interests in light (from Bohr) and botany (from his days in

Bristol) resurfaced in his choice of the phototaxic response

of the fungus Phycomyces as a model system for sensory

perception. Delbruck lectured on Phycomyces to the CSH phage

course in the early 1950s and in the 1960s he initiated a

Phycomyces course there. But in this case Delbruck

oversimplified his problem. The model system he chose did not

have

enough in common with vision for it to provide much in the

way of useful insights into more complex systems. In

particular, the lack of sophisticated photoreceptors and

neurons created a qualitative gap between Phycomyces and seeing

animals.

Home Page

To Life Map